Hundreds of generations over tens of millennia have observed the night sky’s wandering, pale red dot with fascination, but it is only in the last tens of years that we have begun to know Mars as a world. Though far removed from nineteenth-century dreams of sweeping vegetation and colossal canals, the Mars revealed to us by our exploration is in many respects hauntingly Earthlike: mountains taller than Everest and canyons deeper than the Mariana Trench; rose-pink skies and sea-blue sunsets; and everywhere, from scales of hundreds of kilometres right down to the sub-centimetre, the tell-tale calling cards of water.

Water, that is, from several billion years ago. Mars today is the rust-red desert made familiar to most of us by the Hollywood blockbuster The Martian: frozen solid at average temperatures of -60 ºC, and with air pressures so low — a hundredth that of Earth’s — a human’s blood would literally boil beneath their skin. But this cannot have held true for all martian history, else how could the dried-up rivers, lakes, and maybe even oceans we find evidence for have formed? In fact, this is one of the longest standing problems in martian research: what was the early atmosphere made of, and how did it sustain itself?

The modern martian atmosphere is almost entirely carbon dioxide with seasonally fluctuating levels of water, along with trace gases like nitrogen and argon. But no climate models can recreate above-zero temperatures with this composition even at Earthlike pressures. Perhaps some of the usual-suspect greenhouse gases — methane maybe, or sulphur dioxide — propped up these main constituents? Disconcertingly, all show negative warming effects when plugged into models… but for one.

Hydrogen is one of the most common planetary materials, found everywhere from volcanic eruptions to hydrothermal vents. When inputted into the latest models in only trace amounts, it reveals itself to be extremely climatically potent even under a very thin atmosphere. At last, a solution! But, there’s a snag: no known mechanism can account for even modest amounts of it.

A Curiosity for Oxford scientists

A separate story now comes into play, one involving an endearing robotic explorer: NASA’s Curiosity rover. She’s smarter, better-travelled, and chunkier (about the size and weight of a Mini Cooper) than any other five-year-old you’ll ever meet, and she’s spent the past half-decade time-travelling across the beautiful Gale Crater. Here features including mudstones, deltas, and water-bearing minerals provide irrefutable evidence that this crusty dustbowl was once a deep, long-lived lake. But, last year one mineral was found in abundances that puzzled our robot friend: magnetite, which as the name suggests is magnetic — hence iron-rich — and forms mostly in lava flows. What were swathes of this mineral doing at an erstwhile lake bottom?

In a startlingly fundamental yet barely studied process, a team led here in Oxford discovered that the magnetite formed by reacting crater rock (basalt, or lava) with lake water under room temperatures. In this process, iron in the rock reacts with oxygen in water to form magnetite. A simple, satisfying solution to the curiosity of magnetite’s unusual abundance. But take a moment to contemplate the chemical formula for water: H2O. If iron is taking away the oxygen, what remains?

At last: perhaps a source for the modeller’s hydrogen.

The question now remains: how much hydrogen can be produced by this process? If this magnetite production happened in other lakes, could hydrogen emissions have been enough to affect the climate? Could, perhaps, a positive feedback effect have occurred, where an atmosphere sustained by gases emitted from lakes in turn sustained those lakes by maintaining an atmosphere?

And greater questions still are raised: hydrogen is consumed as an energy source by microbes independently of the Sun in the world’s deep places, and on Mars we have found a warm, mineral-rich, water-rich, and now energy-rich environment. Never mind the climatic potency of hydrogen: what about astrobiological?

Mars is no longer that pale red dot of our ancestors: it is a place, and a world. It is easy to let imagination get the better of more rational scientists than this one when it comes to facing an old planetary mystery in the eye. But as I spend the next three years of my D.Phil attempting to understand the magnetite-hydrogen link on Mars, I’ll certainly be holding these greater ones close in my mind.

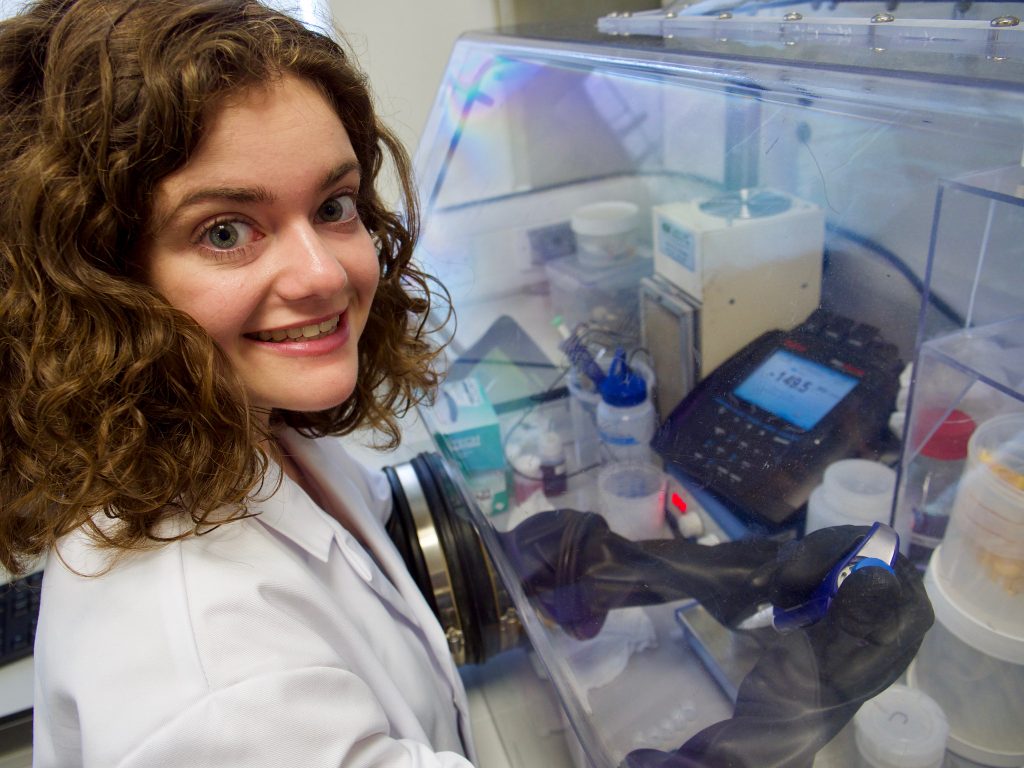

Image 1: The author recreating the surface of Mars in Oxford’s Department of Earth Sciences. All work must be conducted in glove boxes to minimise oxygen (a very unMarslike gas) and prevent contamination by microbes (also — as far as we know — unMarslike).

Image 2: Gale Crater, Mars, where the hydrogen-forming process has been inferred. The fine-grained rocks in the foreground record the quiescent waters of an ancient lake, while in the distance, a great hill of more rock awaits exploration.