By Poppy Jones-Little, MFA (Master of Fine Art)

‘The lumps give up their lumphood, so to speak, before they can become the statue.’

I encountered the term ‘lumphood’ in 2016 when reading through ‘Substances and Universals in Aristotle’s Metaphysics’ by Theodore Scaltsas. Unfortunately the book provided no further insight into ‘lumphood’, and so I began sifting through various texts which also utilise the word ‘lump’. From Marx’s lumpenproletariat to Virginia Woolf’s short stories, from parenting books to Biblical teachings, from Ontology to Oncology, a lump transcends disciplines and refuses classification.

What exactly is a lump?

Reclaimed clay slurried & cast as bellybuttons

Perhaps a return to basics might offer some clarity.

I have compiled the most common definitions of ‘lump’ below:

Often understood as an indiscriminate piece of matter, or a weighty mass; a bulbous swelling or protrusion, especially one caused by injury or illness. You may encounter a lump of coal, clay or iron ore, perhaps even a lump in your custard, yoghurt or cake batter. A small cube of sugar is a lump, and a clumsy, lazy or lethargic person may also be called a lump. Lump was the name of the sausage dog who lived with Picasso for a number of years. ‘To lump’ people together is to disregard individuals as an indiscriminate mass or group; to treat without regard for particularities. But ‘the lump’ may simply refer to the mass majority of people as a united bunch, or even just the ‘lump sum’ of something. You might feel ‘a lump in your throat’, that uncomfortable feeling of tightness or dryness.

Essentially, ‘you might like it, or you might lump it’.

Disused drawing board, the back of a photo frame,

fabric from deconstructed chair, staples and wood

‘Lump’ sometimes has ‘informal’ written next to it in dictionaries; it is a word that many people have a grasp of without question, and yet find it impossible to pin down. An ‘object of thought’ perhaps, it evokes compelling imagery; you might find that when you try to describe ‘lump’, you feel inclined to use hand gestures, as though trying to manifest something otherwise intangible. Certainly ‘lump’ often acts as a placeholder; it is uttered when the right word cannot be recalled. A lump is neither here nor there; not ‘something’, but not nothing — rather a ‘non-thing’.

When thinking about the long stream of inferences above, it becomes clear that almost all of them evoke negativity — feelings, actions, states of being which are lowly, unworthy, wretched, unwanted — and this is just within the English language.

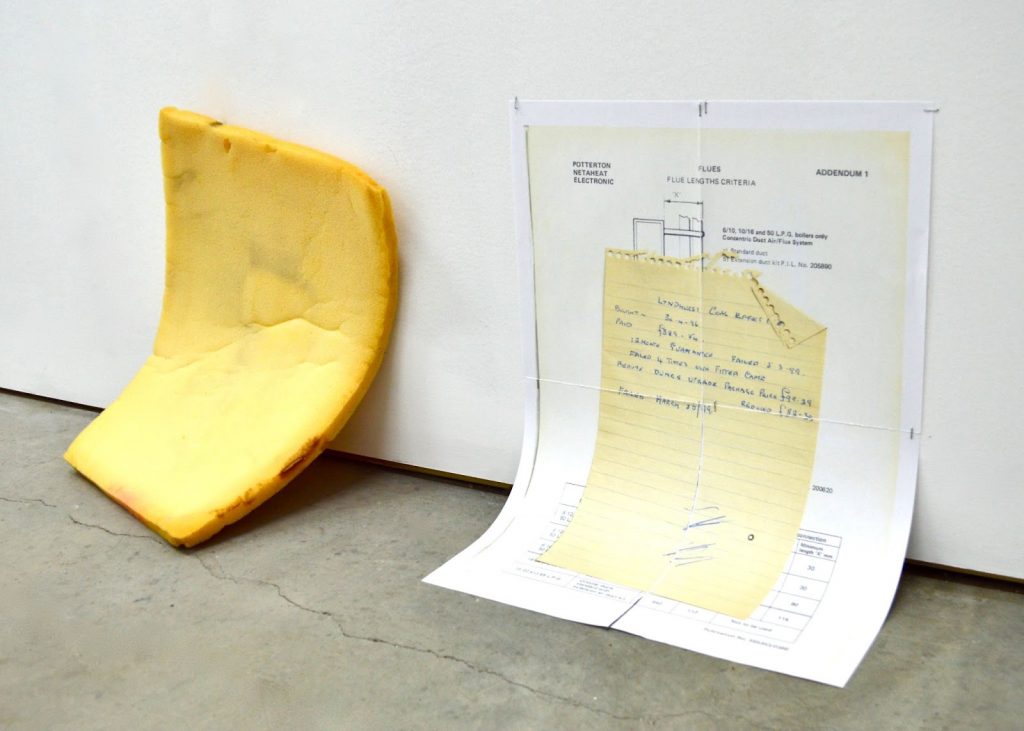

Scanned, rasterised & printed document, staples,

found foam.

Carl E. Pickhardt’s 2007 parenting book speaks of ‘developmental lumphood’; supposedly a stage that adolescents enter into, becoming ‘frustrated […] that there is nothing to do’, they are in waiting to become energised again. It seems that to be a lump is to be without any immediate use or purpose, lumps need to be activated in order to be of any worth – you must ignite the coal, dissolve the sugar lump, mould the clay — otherwise these lumps sit in waiting, in nothingness, in lumphood.

Overlaid, translucent JPEGs of deconstructed table.

It amazes me that a word which usually goes unnoticed is so loaded.

‘Lump’ reminds me just how crucial deep and active listening is; the importance of distinguishing something from nothing, of being hyperaware of not only sound or speech, but the noise which surrounds it. Pauline Oliveros’ speaks of ‘encountering the vastness and complexities’ of soundscapes, of being thoughtful and open. To practice deeper listening can be disconcerting; being so aware of yourself in relation to others, and breaking down usual habits (like automatic replies) may be uncomfortable. But, it is important. It is important to know how and when to use your voice, and when to be quiet. It is essential to step back sometimes, to really listen to ourselves, to pick apart words or phrases that we use in passing, and consider what we are really paying reference to.

And so I ask again, what is a lump?