By Celeste van Gent, MSt Medieval History

In the late summer of 1478, a man named William Worcester set out from Norwich headed for Cornwall. We find him on the road, his saddlebags packed with travel goods like onions and biscuits, laces and packthread, candles, ink and paper. His trip was both ordinary and adventurous. We know he visited bishops and churches, as well as caves and moors. Much was straightforward, but the uncertainties of travel appear here and there. At some point he was arrested, possibly extorted by a forester, and we know when crossing Bodmin Moor, Worcester’s travel companion—his horse—fell down, perhaps both then limping their way to the next town.

A familiar image of medieval travel, especially to those who enjoy historical fantasy literature and film, is that of a lone rider and horse, cloaked, armed, with an assortment of essentials strapped to their saddle, riding hard across an expansive landscape. This is not so unlike Worcester, though perhaps with a bit less drama. Travelling by horseback pervades our sense of everyday life in medieval England yet it goes by largely unquestioned. My research tries to access these moments of ordinary life, for there is much we don’t know.

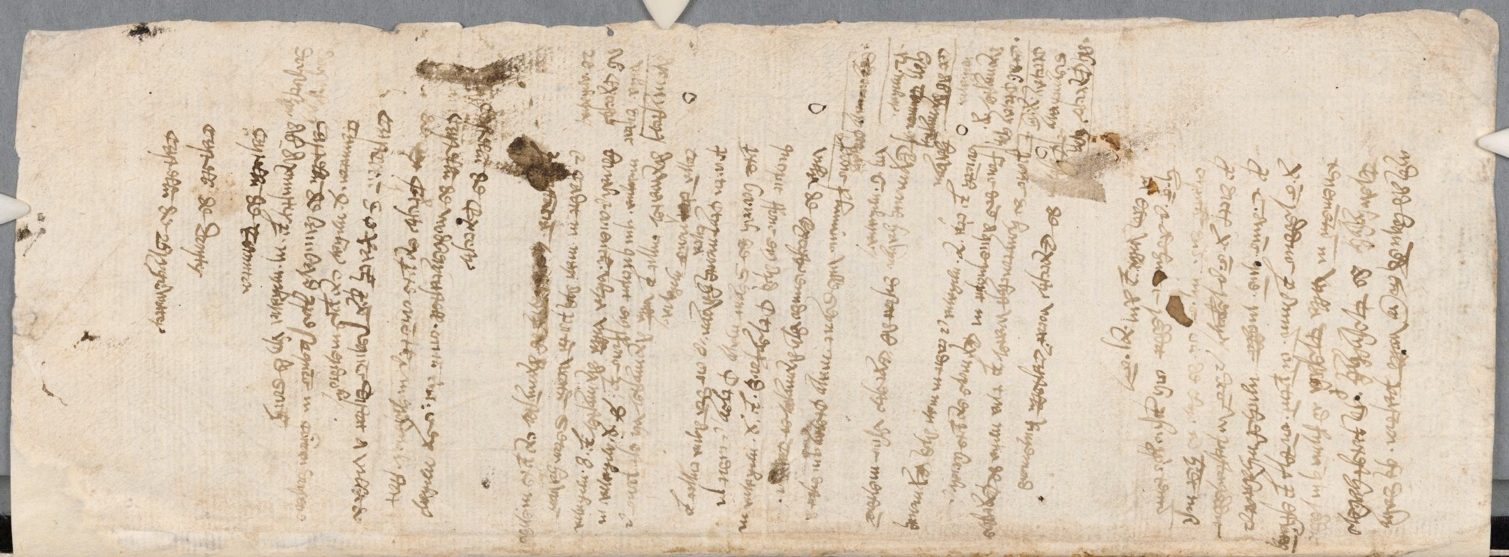

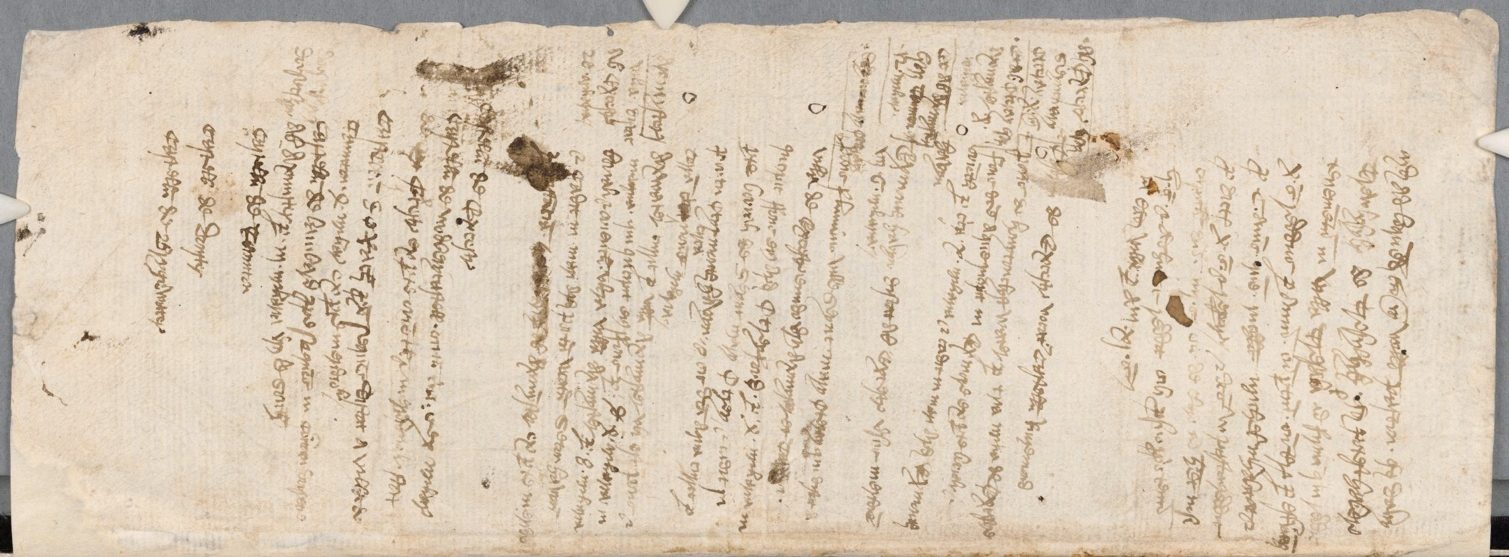

Worcester offers us a unique perspective. He undertook several long but local journeys between 1478-80 and recorded these trips first-hand, producing what is now known as his itineraries, housed in the library at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. They are unique in several ways—only one manuscript copy exists, on long thin sheets of paper that folded neatly into his saddlebags. Worcester recorded the ordinary expenses of his travel including food, shoeing and saddle repairs, the inns he stayed at and the churches he visited. But Worcester was also drawn into the landscape. He meticulously notes rivers, where they flow down from and where they can be crossed. He notes unusual features in the landscape like caves, but also cliffs and rocks along the coast, and the local legends attached to them. From his untidy, hurried scrawl, we can tell he wrote these things down on the spot. Alongside these details, his itineraries are peppered with extracts copied from books housed in the churches and monasteries he visited. He writes down accounts of battles, the lives of saints, the deeds of nobles—we get fragments of Roman history, whispers of Arthurian legend and the memory of local knights. It appears that Worcester was producing a kind of historical geography of England. And my research questions this intersection—asking how did Worcester’s experience travelling across the natural and built landscapes of late medieval England inform his understanding of England’s past? Worcester’s encounter with the landscape is tied to the history he records. There is something significant about the lived experience of his travel, of riding on roads and bridges, navigating forests and fields, and catching sight of cliffs and hearing local legends, to the history he recorded and his vision of England.

To me this topic is not only fun, but important. It engages with environmental history which recognises the influence of the natural world on human history—growing ever more pertinent as we grapple to understand and address our climate crisis. It asks questions of environmental agency, questioning how the path of rivers and forests affected Worcester’s route, or what happens if the moor was boggy and impassable, or indeed how the living animal he rode influenced his going. The topic’s significance for medieval history lies in recovering an untold story, and the under-addressed and elusive thing of local travel and wayfinding. And it helps to understand more fully that idea of the medieval horse and rider as real—contextualised and historicised—not only as fantasy.

Sources:

William Worcester, Itineraria. MS 210 Fol.16r. Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.