As humans living on one fragile planet, how are we to view one another, our diversities and complexities, and where are the vocabularies that help us flesh out a full-bodied understanding of an interconnected, functioning worldwide human community? Are there systems of education that can cultivate such visions and vocabularies?

The vocabulary of poetry might lead us somewhere. Consider Maya Angelou’s words in ‘A Brave and Startling Truth’ where she addresses readers as ‘we, this people’, and explores how we can be both tender and healing with our hands, but also cause such destruction and chaos. Similarly, the Chinese philosopher of the Ming Dynasty, Wang Yangming, poetically asked ‘is there any suffering or bitterness of the great masses that is not disease or pain in my own body?’ Such pockets of artistic and philosophical expression can offer us creative language concerning our common humanity.

Turning to the rhetoric found in international relations, we find vocabulary clothed in Supranational Organisations’ visions. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, for example, offers words which call for worldwide recognition of all humanity as endowed with equal and inalienable rights. Yet it is a vocabulary which some argue primarily draws upon western philosophies for universalism, and is not inclusive of the world’s diverse knowledge systems and practices.

Moving to educational vocabularies, how can we trace and identify such elusive ideals that are at once poetic and philosophical, rooted in our cultural and artistic imaginaries, yet rootless in their political rhetoric, and treacherously abstract?

Such a question may take us to discourses employed by The United Nations Educational and Scientific Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which enshrine the curious ideal of global citizenship (GC) in SDG4, concerning access to education. They offer a mildly agreeable, yet abstract, definition of GC, referring to it as a ‘sense of belonging to a broader community and common humanity. It emphasises political, economic, social and cultural interdependency and interconnectedness between the local, the national and the global’ (UNESCO, 2015, p.14). However, whilst UNESCO certainly has a key, and some might argue hegemonic, role in shaping these global discourses and vocabularies, it is not the sole voice which expresses language resonant with GC ideals.

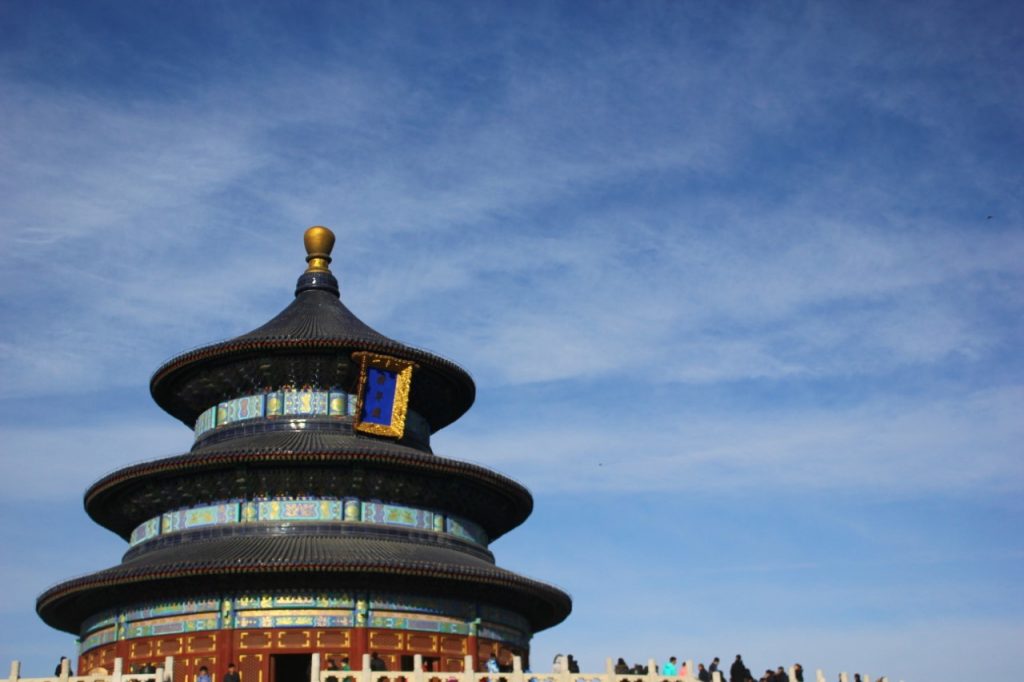

This is where I enter the conversation with a project that looks at the diverse expressions of global and world citizenship education (G/WCE) at the grassroots, in a Chinese higher education institution (HEI). Why China then? Particularly with its complex historical, political, philosophical and social realities, its strong stance on loving the motherland (ai zu guo, 爱祖国), cultivation of patriotism as a virtue, as well as resurgent nationalistic sentiments, some might argue that it is the very opposite of G/WCE ideals. Indeed, Chinese HEIs are heavily influenced by these contextual dynamics, and continually embed themselves within the modern colonial imaginary, through participating in university world ranking systems, actively implementing English taught programmes, as well as promotion of, at times, harmful, internationalisation practices. Yet the political and social re-interpretation of Confucian philosophies that speak of ‘The Great Peace’ (da tong, 大同) and ‘All Under Heaven as One Family’ (tian xia yi jia, 天下一家) through repeated use of the term ‘building a community for the shared future of mankind’ (gou jian ren lei ming yun gong tongti, 构建人类命运共同体), the moral emphasis on family and community, and the great importance that education holds for Chinese civilization, create a landscape of curious and explorable dynamics which may express different visions and vocabularies of G/WCE. Whilst there are presently no G/WCE courses in Chinese HEIs, there are a growing number of research centres, articles, academics, and student movements striving to produce and engage with these discourses, yet mold it into a vocabulary that resonates with China’s layered context. Indeed, these ideals are becoming less abstract, as the current global crisis of COVID-19 is challenging educational communities to flesh out these visions and vocabularies of G/WCE. Yet still, how do you empirically study the conceptually slippery G/WCE in Chinese HE? This is where ethnographic tools and cross-cultural sensitivity come into play: I must listen closely, orient my person and study to the particular Chinese HEI I will be working within, and sensitise myself in the Chinese literatures, both artistic and academic, thus becoming attuned to the voices of the communities I engage with. Indeed, in our present global condition, with a messy humanity navigating the spread of COVID-19, perhaps there is all the more reason to explore how to unveil and sanitize our visions and vocabularies, in order to develop a G/WCE that allows us to see one another as humans, living together on our fragile planet.