As an Educationalist, I have had to endure questions from non-specialists that allow me to prove that I am not training to become a teacher, but I am trying to provide new insights that challenge the way teachers do the teaching. Hence, my interest pedagogy, but more specifically in critical pedagogy. The focus of my research examines how the role of education, through academic exchanges in the classroom, can work as a double-edged sword. It illustrates how the complex role of pedagogy can foster conformity and compliance to traditional modes and structures, but yet in the same vein could conversely cultivate and nurture critical consciousness to challenge the status quo. More specifically, by understanding the dynamic which pedagogy holds in the classroom, I am interested in its impact on students’ academic journeys. Furthermore, my research seeks to analyse how the manifestation of classroom discussions and the trajectory of the educational exchange among peers and professors add to the formation of a student’s political identity in Turkey.

Education is a nexus between the economy, the political sphere, and the wider society. By harnessing it as a proactive tool, drawing from the Freirean understanding of the emphasis on critical pedagogy, one may link the emancipatory nature of such educational philosophy as a reflection of one’s surrounding environment. As an emancipatory tool, Freire’s notion of critical pedagogy seeks to develop social and political consciousness, which is what my study aims to understand during the formation process in an adolescent’s university years. Grounded by a continuous process of self-examination, critique, and reform, critical pedagogy seeks to utilize an education which is propelled by the pursuit of freedom, equality, and justice to deepen the ground of democracy. Therefore, the ultimate roots of social change lay in the epicentre of academia, which manifests in pedagogy. The focus of the trajectory of societal change thus comes from individual formation and the link that one creates to their positionality on the political spectrum through critical consciousness. By underscoring the theoretical lineages that are bound to critical pedagogy, Tarlau (2014) also draws attention to understanding the field as twofold: first, in terms of deepening social theory by analysing formal education institutions as an ‘ideological state apparatus’ (Althusser, 1984). And secondly, by offering educators tools that can be used to help students reflect on political and societal realities (Tarlau, 2014). As such, topics like academic freedom and self-censorship are also highlighted in my study as subthemes while I examine what the converse effects of what a lack of critical pedagogy perpetuates.

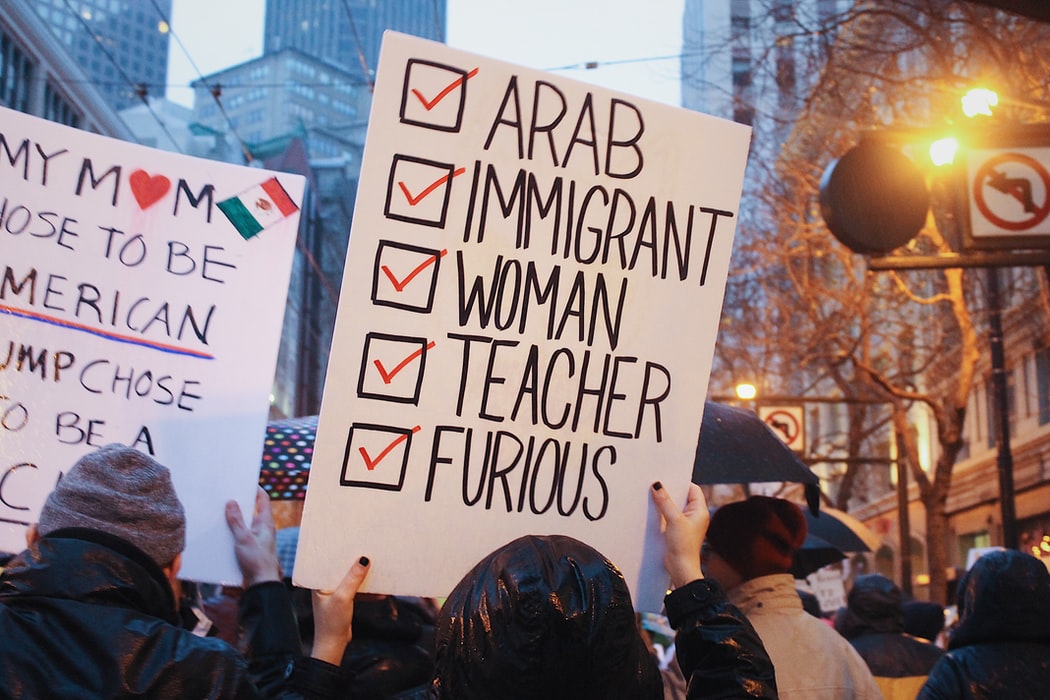

By delving into the waters of academic freedom in higher education, one relies on a democratic plurality reflected by students and scholars’ expression at university campuses as they are not ‘collateral causalities’ of authoritarianism, but in heightened state of affairs may bear the brunt of such policies, as examined in the Turkish case. According to the Middle East Research and Information Project, the crackdown on academia increased after the 2016 government intervention with the repression of a group of anti-war university professors and scholars who became known as the ‘Academics for Peace’. This sort of imbalanced power dynamic between the state and the educational sphere in Turkey has created a climate of self-censorship which has had a detrimental impact on the critical consciousness of students as they engage in classroom discussion at university. As a significant component to fostering democracy and participatory citizens, academic freedom is often one of the first targets of authoritarian policy. Therefore, by unpacking and revealing the reactionary link between draconian policies and the educational sphere, one may observe how students’ critical consciousness is affected by such populist rhetoric.

As such, the dependence to governmental funding in higher education systems could also be viewed as a potential soft-power instrument to further national policies. Therefore, my research portrays a sensitive barometer of a government’s position towards the themes of academic freedom and censorship. The dependency to governmental funding will also be reflected through participant responses from students at public and private universities. Moreover, the principal aim of this research is to explore whether methods of teaching and learning deliberately subvert or strengthen mainstream discourses that may be propelled in classroom discussion. Thus, by investigating the student and teacher relationship, I am interested in understanding how or if the deconstruction of the mainstream narratives in the field of social sciences invites students to problematize and critically challenge such notions. As such, my empirical study will be qualitative research in which I will ask participants through semi-structured interviews, questions related to themes of post-truth, critical analysis, open-mindedness, and draw a comparison to how they relate their educational exchange in the classroom to their interpersonal growth and political identity formation.